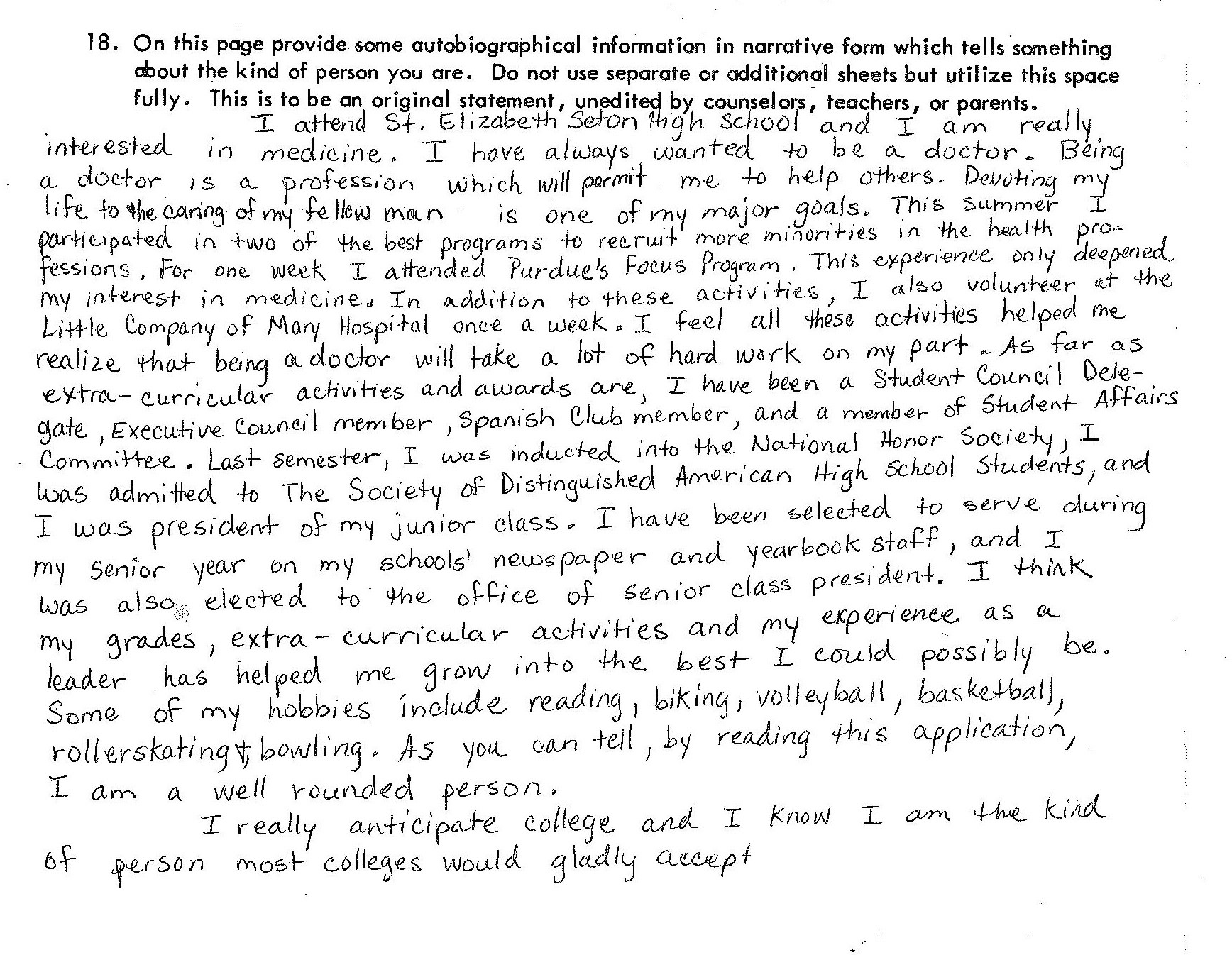

The handwriting is neat and legible, the tone modest but confident. The message is of an ambitious high school senior intent on becoming a doctor, who knows she must persuade someone to help pay the considerable college expenses that such a goal will require.

By the standards of handwriting analysis alone, Sabrina Kendrick’s 1981 application for a scholarship from the George M. Pullman Educational Foundation would probably have been approved. Everything communicated in the essay—her high school accomplishments, her organizational skills, her ability to list achievements without seeming boastful, her bold ambition—is reflected in the person she is today, a veteran infectious disease specialist at Stroger Hospital (a public, urban teaching hospital in Chicago) and an assistant professor of medicine at Rush Medical College.

By the standards of handwriting analysis alone, Sabrina Kendrick’s 1981 application for a scholarship from the George M. Pullman Educational Foundation would probably have been approved. Everything communicated in the essay—her high school accomplishments, her organizational skills, her ability to list achievements without seeming boastful, her bold ambition—is reflected in the person she is today, a veteran infectious disease specialist at Stroger Hospital (a public, urban teaching hospital in Chicago) and an assistant professor of medicine at Rush Medical College.

(Click on the essay to view a larger version.)

Reading the essay, one wouldn’t be surprised that Kendrick achieved her childhood goal of becoming a doctor. But the journey wasn’t as easy as her essay suggested. An only child whose father died when she was just five months old, Kendrick was raised in the South Shore neighborhood by her mother, who instilled in her the values of education and hard work.

“One thing about my mom,” said Kendrick. “She tried to make my life seem normal. It seemed like she was my mom and my dad.”

She describes her South Side youth through the “it takes a village to raise a child” lens, in which she spent plenty of time with neighbors and relatives while her mother worked as an administrative assistant in the Loop. “I never felt like I was deprived,” she said. “I had my family. I had my neighbors. And my mother was such a huge presence in my life. She just made things happen. I don’t know how, but she did. I didn’t have as much as other people, but I had what I needed to get by.”

Kendrick made things happen, too. When it came time for high school, she chose Elizabeth Seton, an all-girls Catholic school in South Holland (now Seton Academy). There, she excelled in the activities mentioned in her Pullman Foundation Scholarship essay and plunged into the business of becoming a doctor, mainly by participating in the Chicago Area Health and Medical Careers Program (CAHMCP, pronounced “Champ”), where she took college-level science courses on the Illinois Institute of Technology campus.

Upon graduating, most of her friends went to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Kendrick was the only one in her class to attend Northwestern University in Evanston.

“I don’t think I was a super-achiever,” she said, “but I knew I could work hard. Academics were easy for me.”

What wasn’t easy was paying the tuition and expenses that come with attending a university of Northwestern’s caliber. Hence the essay and the Pullman Foundation Scholarship, which Kendrick received from 1982 to 1986, covering the four years of her undergraduate experience.

“The scholarship gave me the foundation I needed to succeed,” she said. “It was part of how I was able to go to college. It allowed me to study worry-free, to be successful in school, and work toward my goal of becoming a doctor.”

She had other scholarships, worked part-time, and took out student loans. But the Pullman Foundation Scholarship was the constant, there every year, blunting financial challenges and sparing her from immense debt.

After graduating from Northwestern, CAHMCP gave her pointers about preparing for medical school. In 1986, she enrolled at the Chicago Medical School in North Chicago through an Illinois Department of Public Health scholarship. It offered her a full-ride on the condition that she provide primary care in an underserved Illinois area—rural or urban—when she graduated.

That’s how she got to Cook County Hospital (now Stroger), where she works today. Before starting there, she did her residency at Atlanta’s Emory University hospitals and completed a fellowship at Northwestern in infectious diseases.

It’s been nearly 30 years since Kendrick received the last year of her Pullman Foundation Scholarship. But she hasn’t forgotten the degree to which it forged her life and she remains an active supporter of the work of the Pullman Foundation.

“I was blessed to have the Pullman Foundation Scholarship,” she said. “It got me to where I am because people thought that much of me to give me a scholarship. Just because you don’t have money doesn’t mean you can’t go to college.”